| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

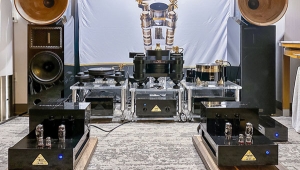

Analog Corner # 247: Dr. Feickert Firebird turntable, Viva Fono MC phono preamplifier, AcroLink and Fono Acustica interconnects

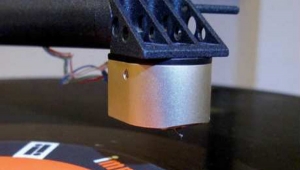

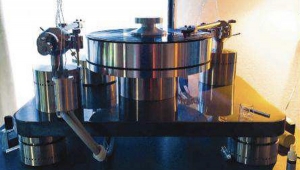

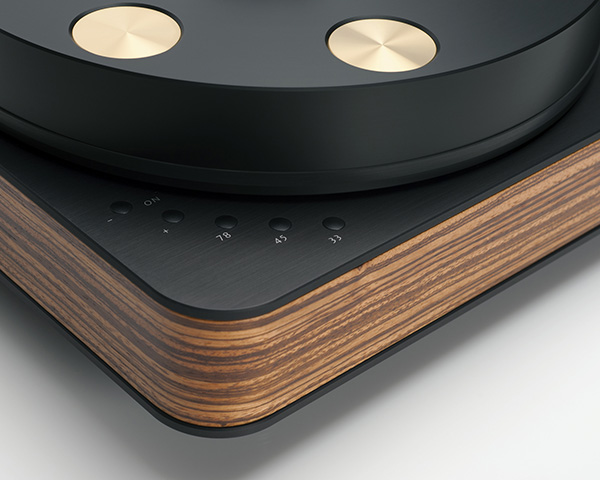

Dr. Feickert Analogue's top-of-the line turntable, the Firebird ($12,500; footnote 1), is a generously sized record player designed to easily accommodate two 12" tonearms. Its three brushless, three-phase DC motors, arranged around the platter in an equilateral triangle, are connected to a proprietary controller in a phase-locked loop (PLL); according to the Firebird's designer, Dr. Christian Feickert, a reference signal from just one of the motors drives all three—thus one motor is the master while the other two are slaves. (Man, today that is politically incorrect, however descriptively accurate.) Feickert says that the key to this drive system is the motor design, which was done in close consultation with its manufacturer, Pabst. The result is a feedback-based system in which the controller produces the very low jitter levels claimed by Feickert.

Footnote 1: Dr. Feickert Analogue, Stegenbachstrasse 25b, 79232 March-Buchheim, Germany. Tel: (49) (0)76-65/9-41-37-18. Fax: (49) (0)76-65/9-41-37-25. Web: www.feickert.com. US distributor: VANA Ltd., 728 Third Street, Unit C, Mukilteo, WA 98275. Tel: (425) 610-4532. Fax: (425) 645-7985. Web: www.vanaltd.com

A complete redesign of the inverted platter bearing used in the Firebird and in Feickert's two other turntables, the Woodpecker and Blackbird, is claimed to reduce the contact area between spindle and bearing well by 80%, in order to reduce friction and, in turn, rumble, wow, and flutter. (Good thing: The original Blackbird, which I reviewed in my September 2011 column, wasn't the quietest bird on the block.) Riding on the inverted bearing is a 13.23-lb platter of polyoxymethylene (POM), which is said to have resonance characteristics similar to those of vinyl itself; embedded within that platter, close to its outer edge, are eight solid brass cylinders. Feickert says that his three-motor arrangement, in which the platter is evenly driven by a thick, precision-ground belt made of nitrile butadiene rubber (NBR), results in a more stable bearing and platter by canceling out "virtually all acting forces," to effectively eliminate bearing and platter wobble.

The Firebird weighs 68.5lb, and its plinth is large: 22" wide by 6.25" high by 18.25" deep. Its thin upper and lower aluminum-alloy plates sandwich a block of treated MDF, and it sits on (newly designed) adjustable feet. The plinth is available in natural or black-anodized alloy, with side panels of zebrawood or piano-black lacquer.

Feickert's arm-mounting system makes installing, adjusting, and swapping out tonearms more convenient than on many turntables. In each rear corner of the plinth is a large, oval, diagonally oriented cutout; the one on the right can accommodate arms with effective lengths of from 9" to 14", the one on the left arms of 9" to 12". Each cutout can be fitted with a circular armboard that bolts to a pair of sliding, captured nuts, one nut on each side of each cutout. A notch in the rim of the armboard aligns with a scale calibrated in millimeters and silkscreened on the plinth, for measuring the distance from the tonearm's pivot to the center of the platter's spindle—obviating, in most cases, any need for a pivot-to-spindle protractor. This makes swapping tonearms easy, assuming you've already mounted your other arms on Firebird armboards and that their pivots coincide with the centers of those armboards. Otherwise, as with tonearms that have off-center pivots—eg, the Kuzma 4Point, the Tri-Planar, and the Reed 3P—you'll need to use a protractor capable of measuring pivot-to-spindle distance. Dr. Feickert Analogue, among others, makes such a protractor.

A single armboard is included in the Firebird's price; to make use of the turntable's second arm cutout, the user must add to it a Delrin "slider" ($100) and purchase an additional armboard ($125 each). The Firebird's platter bearing is warranted for five years, everything else for two years.

Relatively Easy Setup: I placed the Firebird's 68.5lb plinth atop a Harmonic Resolution Systems isolation base, made sure that both base and plinth were level, then attached to the plinth's underside the L-shaped mini-plug for the power supply. After applying to the bearing spindle a decent amount of the supplied lubricant, I carefully lowered the platter into place and waited for it to fully seat itself. That wait over, on went the belt. The only sticking point was getting the armboard bolts into those sliding metal nuts. It wasn't easy, but only those who like to swap arms in and out will have to bother with it.

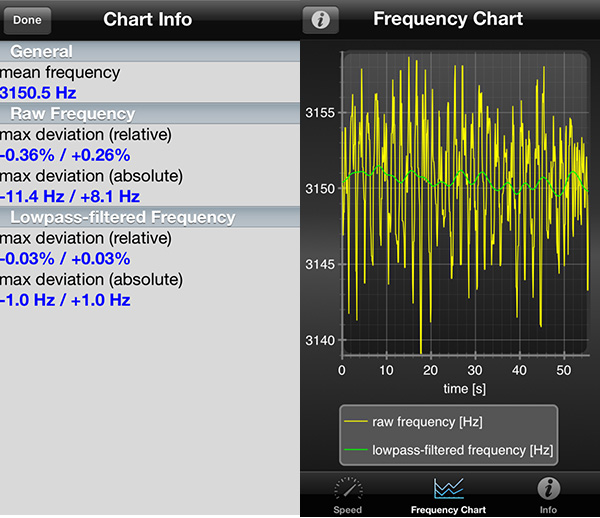

Fig.1 Dr. Feickert Analogue Firebird, speed stability data (left). Fig.2 Dr. Feickert Analogue Firebird, speed stability (right; raw frequency yellow; low-pass filtered frequency green).

The Firebird can spin at 33 1/3, 45, and 78rpm; plus and minus buttons permit easy speed adjustment, if needed. The speed controller comes precalibrated, but I nonetheless checked it with Dr. Feickert Analogue's PlatterSpeed software and 7" test record. All three speeds were spot on, and remained so throughout my listening. See figs.1 and 2 to check out the measured results at 33 1/3rpm: They're very good, and unusually symmetrical (perhaps because of the equilateral three-motor drive system?), though the low-pass-filtered trace (fig.2, wavy green line) seems to indicate the constant correcting action of the controller. Still, the filtered results look good, if not the best I've measured.

Nine Inches—More than Long Enough for Me! Despite their popularity in some circles, I've never been a big fan of 12"—or longer—tonearms. (What were you thinking?) I've long believed that whatever benefits are gained with longer arms' lower theoretical tracking error and need for less anti-skating force are more than offset by their lower rigidity, their amplification of any errors made in setting overhang or zenith angle, and, especially, problems resulting from the arm's greater moment of inertia—ie, a tonearm's ability to handle a record groove under dynamic conditions.

This has also been the conclusion of the designers of Continuum Audio Labs' 9" Cobra tonearm ($12,000) and, more recently, of Marc Gomez, who designed the Swedish Analog Technologies arm ($29,000). In fact, the SAT arm is actually somewhat shorter than Rega Research's own tonearm—long a de facto standard—all models of which have an effective length of 239mm (9.321"). Gomez, who has a master's degree in mechanical engineering and materials sciences, says that whatever tracking-error distortion a shorter arm introduces is more than offset by its greatly superior performance under dynamic conditions. Listening to his SAT arm sufficiently convinced me of that that I plunked down, without regret, five figures' worth of retirement income. Of course, more than its length is involved in the sound of the SAT arm. (That said, I also own and love the 11" Kuzma 4Point.)

So, when Axxis Audio's Art Manzano offered a Reed 3P for review, I chose the 9" version and attempted to mount it in the Firebird's right-hand corner, with my Kuzma 4Point in the left. But that didn't work—the Reed's pivot assembly was where the Kuzma's long headshell wanted to be.

Nor was it possible to mount and conveniently use the Reed arm on the left with the Mørch DP8 arm (9.25" effective length) on the right. These shorter arms have a shorter pivot-to-spindle distance, which puts both of them closer to the platter; when correctly set up, these arms, too, interfered with each other.

So I ended up doing much of my listening with just the very familiar Kuzma 4Point mounted on the Firebird's right armboard. Later, I managed to mount and use the Mørch and Reed arms—but in order to use the Reed on the left mount without it banging into the Mørch, I had to move the Mørch from its rest, then carefully lift the stylus of the cartridge mounted in the Reed over the widely spaced side weights of the Mørch. I was able to use both arms, but not easily.

From all of this, I concluded that while the Firebird is perfectly suited to be used as designed—ie, with one or two 12" tonearms—before buying you should carefully check for its compatibility with whichever two arms you're considering or already own, and know that you'll still be comfortable if your favored arm might have to be mounted on the Firebird's left armboard.

My experience with the Firebird challenged two long-held opinions: First: The best platter motor is no motor at all. But because a platter must be rotated by something, you have to compromise. But why triple the noise by adding two more motors and their pulleys, knowing that it's virtually impossible to machine either to sufficiently low tolerance to prevent chatter? Second: The best plinth is no plinth at all. But, again, you need one, so you'd better make it as small as possible, to avoid a large, resonating surface.

The Firebird has made it clear that if enough design attention is paid to the motors, pulley tolerances, mounting arrangement, controller, and interface between motors and platter, the problems of noise and jitter can be, if not completely solved, then reduced to near-irrelevance, leaving intact all of the benefits Dr. Feickert Analogue claims for the design. In fact, when I placed a stethoscope on the Firebird's plinth close to each of its motors, I heard near silence—and far less noise than I've heard from many single-motor designs I've 'scoped. Same with the Firebird's heavy, well-damped plinth: When I tapped it, I heard near-silence, whether from the stethoscope or my speakers.

In short, if a manufacturer's aim is to make a turntable with a big plinth and the alleged benefits of three motors, it should be done right. In the Firebird, Christian Feickert has. And if your aim is to own a turntable that can easily and competently handle two 12" tonearms, the Firebird is well worth considering. But if you're considering buying or already own a 9" arm or two, spending $12,500 on a Firebird buys you an awful lot of costly, unnecessary real estate.

Footnote 1: Dr. Feickert Analogue, Stegenbachstrasse 25b, 79232 March-Buchheim, Germany. Tel: (49) (0)76-65/9-41-37-18. Fax: (49) (0)76-65/9-41-37-25. Web: www.feickert.com. US distributor: VANA Ltd., 728 Third Street, Unit C, Mukilteo, WA 98275. Tel: (425) 610-4532. Fax: (425) 645-7985. Web: www.vanaltd.com

- Log in or register to post comments