| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

I have a copy of this catalog number- how does one tell whether it's a pre or post 1977 pressing?

and I agree about the Vieux Telegraph- i have a '98 in my cellar.

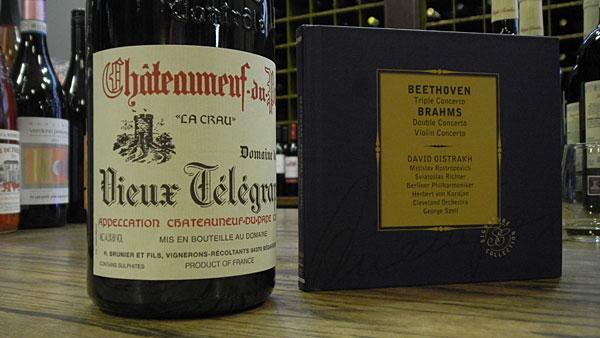

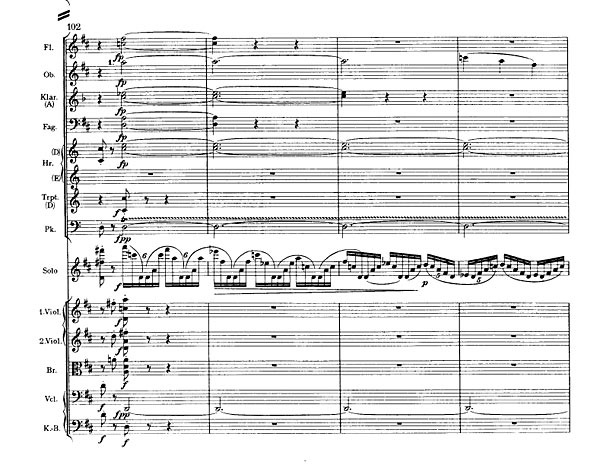

The pick in question is the recording, "remastered at Abbey Road" and bound as a book, of David Oistrakh playing the Brahms Violin Concerto and Double Concerto and Beethoven's Triple Concerto, with cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, pianist Sviatoslav Richter, George Szell and the Cleveland Orchestra (Brahms), and Herbert von Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic (Beethoven) (2 SACD/CDs, EMI Signature Collection 9 55978 2).

Why take back an R2D4? I will explain. First, some necessary background:

I think the informed consensus is nearly universal that, had Iosef "Jascha" Ruvinovich Heifetz (1901–1987, though he may have been born in 1899) never appeared on the scene, David Fyodorovich Oistrakh (1908–1974; né Kolker, he early adopted his stepfather's surname) would have been considered the greatest violinist of the 20th century.

Without doubt, Heifetz brought unprecedented technical facility to bear on major works that previously had not been fully realized in concert performances, most notably the concertos of Tchaikovsky and Sibelius, and Chausson's Poäme for violin and orchestra. That said, Heifetz's legendary "silken tone" was often at the service of interpretations that critic Virgil Thomson once called "silk-underwear music."

As time went on, Heifetz seemed to revel in playing as fast as possible for the sake of speed itself. He also was not above "improving" masterworks that perhaps he felt were not showy or violinistic enough for his agenda. An example of the latter was his adding to the violin part at the end of Franck's Sonata (in a recording with Artur Rubinstein, no less) notes that Franck never wrote—I think, in order to keep the piano from having the last musical word. Heifetz also turned the trill at the end of the Ciaccona, from J.S. Bach's Partita 2, in d, into a double trill—but perhaps that can be excused as a nod to the baroque ethos of improvised ornamentation.

My default posture re: Heifetz has always been to debunk the hype. However, I would never want to be without his (mono) recording of the Ciaccona spuriously attributed to Tommaso Antonio Vitali (1663–1745), which is one of the most thrilling of all violin recordings. I also must say that I was rather shocked at how lyrically unrushed and soulful is Heifetz's 1938 recording of the Glazunov concerto, with John Barbirolli and the London Philharmonic Orchestra. I can only speculate as to why. Was Heifetz temporarily under the spell of Barbirolli's compelling musicality? Or did Heifetz think that while Americans might understand only the fast and the loud, British audiences needed to be conquered with lyricism?

Listen to the Heifetz-Barbirolli Glazunov for yourself; it's available here, or on CD (EMI 61591). It certainly doesn't sound like the Heifetz of the post-WWII RCA recordings. But please keep in mind that I am showing Heifetz in his best light with that.

I think it's fair to say that Heifetz is today remembered more as a paragon of violin technique than as a supremely important and broad-ranging interpreter. There is more to interpretation than just precision of execution. As far as I'm concerned, with Heifetz there is almost always a sense of forward propulsion, sometimes to an uncomfortable degree; with Oistrakh, there is always a sense of musical flow.

Career-wise, Heifetz had the good luck to decamp for greener pastures before the Russian Revolution, ending up in New York City. His 1917 Carnegie Hall debut, at a claimed age of 16, was legendary. Heifetz's performing career in the US was well established before the stock-market crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression.

In 1939, Heifetz costarred in the film They Shall Have Music, playing himself in a story about a struggling music school for the poor; it's worth seeing once. After WWII, and with the advent of the 331/3rpm LP, Heifetz was an undisputed icon of aspirational culture. Along with Einstein's, Heifetz's is one of the few surnames that have become almost common nouns, as in "He's no Heifetz." Heifetz continued to perform and record until the early 1970s; thereafter, he continued to teach for almost 15 years.

In contrast, David Oistrakh was a late bloomer, first on the viola, then the violin. He caught almost every bad career break he could—from coming in behind Ginette Neveu in the first International Henryk Wieniawski Violin Competition, in 1935, to being stuck in the Soviet Union through the Stalin years, WWII, and the Cold War. Oistrakh also ran the risk of being too good a friend to the politically "unreliable" Dmitri Shostakovich. Further, while Heifetz was darkly handsome (after a fashion, at least in his youth), by the time Oistrakh's fame had spread beyond the USSR's borders, he looked like a potato farmer or a Soviet bureaucrat. But the guy sure could play—and play not just the violin, but music. An iconic Oistrakh Bach performance from 1952 can be heard here.

The hallmarks of an Oistrakh performance were a warmly centered tonal beauty, unfailing accuracy of pitch, interpretive humility, understated stylistic elegance, and a nobly monumental conception of the music's architecture. American audiences did not hear him in concert until 1955, at Carnegie Hall—his debut was the climax of a day that had heard both Elman and Milstein play on the same stage. Autodidact culture vulture Marilyn Monroe was in the audience.

On his first US tour, Oistrakh recorded with Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra, and soon recorded with Dimitri Mitropoulos and the New York Philharmonic, as well as Charles Munch and the Boston Symphony. Oistrakh's recording with Mitropoulos was the first of Shostakovich's magisterial Violin Concerto 1, which was dedicated to him.

Oistrakh recorded the Brahms Violin Concerto at least four times in studio settings: with Kiril Kondrashin (Moscow, 1952), Franz Konwitschny (Dresden, 1954), Otto Klemperer (Paris, 1960), and Szell (Cleveland, 1969). (As many as 10 live recordings, in varying degrees of sound quality, have also been available over the years.) I've always thought the recording with Szell was the best of the bunch. First, it's in stereo (as is the Klemperer). Second, in 1969 the Cleveland Orchestra was at its peak under the legendary, and legendarily difficult, Szell. And while Oistrakh was then in his 61st year, his technique was still effortlessly solid. And in 1966, he had finally settled on the 1705 "Marsick" Stradivari as his ideal instrument.

Scratch One R2D4

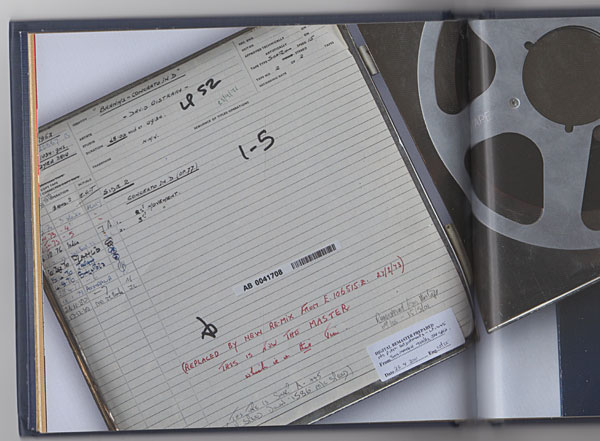

So it seemed to me a no-brainer to name the SACD remastering of the Brahms-Oistrakh-Szell-Cleveland (BOSC) recording as one of my R2D4s for 2014 (though I knew it was from a PCM transfer, and not a direct DSD transfer). But as soon as the February 2014 issue hit the mailboxes, things began to unravel. Sharp-eyed reader and former broadcast engineer Richard Lane e-mailed to say that he'd noticed that the inside-cover log sheet of the tape box pictured in the SACD booklet (see photo) stated that the tape in that box was a replacement "Re-Mix" that was "Now the Master." Yikes!

Lane wanted to know whether that March 1973 master-tape substitution was perhaps the cause of the overloads he heard in orchestral tuttis. I had always heard the momentary overloads in the tuttis, but had assumed they were artifacts of the master tape. For me, at least, they didn't detract from the beauty of Oistrakh's tone in the solo passages, or make this bargain-priced ($20) two-SACD set, on the whole, less recommendable. But . . . hmm.

I scanned and blew up that page of the booklet, and was horrified to see a smaller notation: the tape had seemed musically sharp to one EMI engineer, with concert A at 445, not 440Hz—which therefore made the entire performance not only sharp but too fast. A directive in reply, dated 2011, stated that there were to be no speed adjustments, in that the "LP=445." Double Yikes!

That was when I began to suspect there was something not quite kosher in Denmark. My violin teacher at Brown, Professor Kowalski, once asked me to guess when A=440 had been established as the international tuning standard. I guessed the 1860s or 1880s. He replied that it had been 1936. Indeed, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) did not establish 440Hz as the international standard until 1955.

Before 1936, concert pitch was usually (but not always) A=432Hz. The notion that Oistrakh was tuning to A=445 or higher struck me as absurd. And the idea that the Cleveland Orchestra would tune to A=445 struck me as even more ridiculous, given that the Boston Symphony was always regarded as out of step with other American orchestras for tuning as high as A=442.

I consulted with classical recordist and world-class Mahlerian Jerry Bruck, who advised me to enlist the aid of the Historical Committee of the Audio Engineering Society. Tom Fine, an engineer in his own right as well as the son of C. Robert and Wilma Cozart Fine, the couple responsible for producing and engineering the Mercury Living Presence recordings, responded with an open-ended offer of help. I'll bet he had no idea how long this would drag on.

My next step was to phone the Cleveland Orchestra and speak with archivist Deborah Hefling, who promised to ask current and retired players. The answer quickly came back: The Cleveland Orchestra has always tuned to A=440. Therefore, the EMI SACD whose CD layer I had, measured as A=446.4 or 446.5Hz, using the Amadeus Pro II app, was from a "corrupt source." The result was the same with the 24-bit/96kHz hi-rez download.

Then as now, I was less concerned about the digitized tape's not being the "original master" as I was about the tonal and interpretative misrepresentation of the music resulting from its being played back faster and sharper than these musicians had performed it during the recording. On the speeded-up SACD, the first movement ends about 20 seconds faster than it must have in real life. I think that's a nontrivial musical difference.

I have a copy of this catalog number- how does one tell whether it's a pre or post 1977 pressing?

and I agree about the Vieux Telegraph- i have a '98 in my cellar.

I believe that if your pressing has a scribing in the dead wax area something like S 1 36033 A 1 or S 1 36033 B 1 or S 1 36033 C 1, it was cut from the original edited stereo mixdown true master tape.

The Angel, "Mastered By Capitol" (a stamping in the dead wax area) pressing I bought in Nashville in 1977 is scribed S 1 36033 F 13 #2, from which I infer but it is only an inference that its source was an acetate that was the sixth ("F") US cutting. Because it too is fast, I conclude that at or about the same time the UK master was replaced the US master was replaced too.

So now we just have to hope that the original US master was not thrown out or recorded over.

jm

is what mine says- what does the 4, or 13 #2 signify?

in any event, it sounds the same to me as the Classic reissue. i Heifetz SACD, and Perlman/Giulini CD, and Grumiaux/Davis on vinyl. as a performance my preference has always been Perlman/Giulini, which i prefer to his later recording w/ barenboim.

The LP replication process goes (1) cut acetate, (2) negative master, (3) matrix or mother, and (4) stamper.

As far as I know, a cut acetate makes one negative master which makes one matrix which can make several stampers before it wears out and a new cutting is required.

So I believe that the stamper that stamped your LP was the fourth stamper made from the sixth acetate. Seeing as that acetate is the same as my LP's, that should mean that your LP is fast and sharp too.

JM

That might provide the answer as to what happened to the original. Producers might recall these kinds of things where the labels and label archivists do not.

As for getting the music properly re-done (assuming the better sources can indeed be found) the only person I've read about who's had success where others have not is Chad Kassem. My understanding is that he shows the labels a combination of cash and perseverance other people don't. And that gets answers, at least.

That said, apart from pitch, the overloading is the main sonic problem? Let's say overloading isn't due to the 2nd or 3rd gen ('73) tape. Pitch and speed can be corrected with software but of course that's not the sort of homework a buyer should be expected to do for a R2DF candidate.

The first thing that you must understand is that the company EMI no longer exists. It was broken up and the classical division went to Warner; I have had no luck getting a response from anyone at Warner or at Capitol Studios. I have also reached out to some former employees who either ignored me or had no information.

Two, as a general rule, in a big label (unlike a small label) once the recording is in manufacturing, the recording engineer moves on and the producer moves on. In this case the recording engineer died some time ago. Tom Fine shared with me much information about Carson Taylor's work methods at the time, and the Cleveland Orchestra scanned copies of a logistics and scheduling document, but that was all 1969, NOT at the time of the master tape substitution.

In theory, there might be a paper trail in dead storage wherever EMI ancient history is stored, but in fact all that might have been sent to the landfill or recycling. The session producer died some time ago, again, not surprising, as recording Soviet musicians with an American orchestra was the most important thing EMI had going on at the time, so they used their top people, whose careers had started in the 1950s. The in-machine Cleveland master tape, if it still exists, is more than 45 years old. Visualize the final scene of the first Indiana Jones movie, and you will not be far from what my experience has been.

Over and above that the trail is cold, the reason why there was a "remix" that resulted in a master tape replacement ultimately is only academic because it was wrong. The troubling word is "re-mix." To me, that indicates that there is a strong possibility that someone somewhere went back to the in-machine Cleveland master and did a new stereo mixdown. So, to get at the sonic truth, we need either (1) the in-machine Cleveland master and either a working Dynatrack playback setup or a means to effect those "Boosted-to-NAB (and back)" track changeovers in the digital domain, or (2) Carson Taylor's original, correct-speed stereo mixdown razor-blade-edited master tape. In an ideal world. I'd prefer the first option because that would allow a more natural balancing between soloist and orchestra.

I have discussed this recording with Chad Kassem several times. He is not interested, and I can understand why. Chad is a Blues guy. More importantly, this is not a sonic blockbuster like Scheherazade or Symphonic Dances. It is core classical repertory. There are at least 80 violinists represented on non-historical discs, with many, like Oistrakh, having more than one performance (4 studio, as many as 10 live). So Arkivmusic.com lists 195 Brahms Violin Concertos. Now, what an entrepreneur could do is Kickstart the project and not pull the trigger and collect the money until the One True Master Tape is found. But that is not Chad's business model and I have no hard feelings.

I don't know why you say "Let's say overloading isn't due to the 2nd or 3rd gen ('73) tape." I have not heard a pre-1973 pristine LP on a good system. I rather doubt that Carson Taylor would have approved an overloaded stereo master--and he, I am told, did his own editing, which, back then, was razor blade and splicing tape. My assumption (yes, it is an inference from established facts) is that in 1973 they played the Cleveland in-machine back not realizing that it required special playback electronics, which is why there is a notation somewhere (I was told by Abbey Road) that there was a tape box in the archives marked "Unplayable." Whether they kludged from that or had some other Plan B, I do not claim to have a clue.

One would think that with all the audiophile-reissue formats this performance has appeared in, there would be remaining demand. But the conventional business model has a break-even at or over 4,000 units, which is why I believe, based on 30 years in the recording business, that Kickstarting is the only solution. As far as I can see, only that gives you a handful of cash to wave in the face of Warner and say, we are ready to prepay the license fees so you don't have to trust us or chase us.

ATB,

jm

John,

Great article. What was the vintage of this Chateauneuf?

Thanks,

Ralph

Hi-I was really not paying attention to the vintages. I went to a wine store and asked if I could pose a bottle with the SACD book and take some pictures. I liked the dramatic high-contrast label and the designation "La Crau," which was as close as one can get to the crow I had to eat.

jm

Ah I see. It is a terrific wine nonetheless and indeed if a crow pie were served up it would pair perfectly. I see one reader below with some 1998 in his cellar which is drinking beautifully.

I'm just getting into SACD down here in the deepest, darkest Rhone Valley (Department de l'Ain), but Chateauneuf? A €5 wine on a €20 budget one might say, whatever the domaine. It's ok if you don't mind your wine tasting like molasses (but then it is a molasse of 13 seppages), but a bog-standard mis-en-bouteille 'Vieux Papes' shows it a clean pair of heels for 1/10th of the cost (I doubt that you'll get it over the pond, mind). Still, in a milieu where people justify paying 10,000s for an ethernet cable or a mains lead, Each To Their Own...

HI. Thanks for posting. The web version omits some aspects of the print version, in this case, the headline "Which Wine Goes Best With Crow?" Although that thought recurs at the very end of the text too.

So, Eating Crow was on my mind when I stopped in at a fancy wine shop downtown and asked to pose a bottle with the SACD book and take some pictures. I chose that bottle because of the designation "La Crau." Given the major expense of that bottle, and the fact that I don't have Sam Tellig's credit card number memorized, I did not buy it.

For my next act I will build and market a mains lead made from worn-out Pirastro Eudoxa Olive Rigid violin G and D strings that were used only on pre-1800 Cremonese violins. Harmonic richness such that you can imagine you are smelling all 13 (or 14) distinct grape varieties in a great CTNDP!!! A bargain at USD10,000 per 2-meter mains lead! Send me your money before someone else does!

Tee hee.

jm

Congratulations on a splendid article and brilliant detective work combined with academic rigour. And yes - the 440Hz snippet sounds much more natural.

Next, you will be telling us that Richter actually recorded his famous 1970/19S73 Schloß Klesheim Melodiya recording of the Bach Preuldes and Fugues at 440Hz too ... even though they sound almost a semitone sharp ! (something I have never understood).

It would be disappointing if it transpires that some engineers back in 1973 thought it 'cool' to tweak recordings to make artists appear, say, more virtuosic ... the way people today might photoshop a photo today to tweak it. Ooh - look what we can do with this fancy-shmancy tape deck machine!!! ....

Separately, as I commented on your original article, I found the SACD transfer by EMI of the Brahms to be highly distorted ... for whatever reason. Unfortunately, the EMI engineers did not simply do a tape to DSD transfer, but ran a whole bunch of artificial digital filters, cleaners and disinfectants over the source file to de-hiss it, ... which rather kills the whole point of transferring it to SACD (which is to keep things au naturel).

I really doubt an engineer took into his head to replace an LP cutting tape prepared by Carson Taylor or under his direction with a speeded up "remix" just because he thought it was a good idea.

One possible explanation is that because Oistrakh had recorded the Brahms in Paris for EMI in 1960, and in 1969 also recorded the Beethoven Triple in Berlin for EMI, the Cleveland tapes were the Odd Men Out in terms of pitch, and some executive decided to speed up the Cleveland tapes so they would sound more similar in pitch to the European tapes, but in so doing they truly distorted the pacing and phrasing.

I am keeping at this; I am trying to get Warner Brothers to do a vault search in California and in England. If a non-corrupt stereo mixdown master is located, or even the multitrack session tapes, then at least a reissue outfit like Mobile Fidelity can evaluate it as a business proposition, and if not, some ambitious person can Kickstart it.

JM

I fail to see why a recording that was classified as R2D4 should be downgraded because it might have been speeded-up. I would have thought that the R2D4 was awarded for what was heard on the recording - and that has not changed.

It is always tricky to determine the pitch at which something was played when the original recording was on analogue tape. This is because there was seldom a good absolute frequency reference, such as we now have with digital recordings.

John Marks makes an assumption that because it is thought that the Cleveland orchestra always tuned to A440 then that must have been the actual pitch used. I have analyzed a few of Oistrakh’s recordings and they are mostly pitched higher than A440.

The recording I have of the Brahms concerto featuring Oistrakh with Kondrashin is at A447, the recording I have of the Brahms concerto featuring Oistrakh with Klemperer is at A445. The Brahms double concerto I have featuring Oistrakh and Rostopovich with the Cleveland orchestra under Szell is at A447. I also looked at Oistrakh playing Mozart and found it to be at A447 as well. The fundamental question is does anybody know with absolute certainty which pitch Oistrakh asked conductors/orchestras to tune to when accompanying him.

It is, of course, possible that most of the Oistrakh recordings that I have (no matter what the label) have been speeded-up by playing the tape a little faster and it is, of course, possible that the original release of the Brahms concerto had been slowed-down by somebody who thought that the Cleveland always tuned to A440. It is also possible that the directive to keep the higher pitch on re-issue had come from performer input after having heard the original release.

The spread of Oistrakh's movement timings, from his various recordings, is significantly greater than 1% (if I remember correctly his spread was greater than 7%).

While I don't have the recordings or software on hand to check these, the fact that Oistrakh's pitch seems to be higher than 440 on several other noted recordings would suggest that this was a habit for him. I would also note that, while the first movement's length of 22:35 would appear to be potentially 20 seconds shorter than it would be if the tape were re-pitched to 440, it barely differs from the 22:36 of his recording with Klemperer, and is slightly slower than the 22:30 of his version with Kondrashin (all timings courtesy of Tidal). Now, maybe every version of Oistrakh's Brahms concerto (along with, as noted above, several other of his recordings), all coming from different companies over the course of several decades, happened to be coincidentally and accidentally sped up by about the same amount. On the other hand, I would have to wonder if, perhaps, the "no speed adjustment" directive, rather than coming from some apathetic EMI "suit" with no expertise in the matter, might indeed have come from a source that had knowledge that the original recording was, in fact, made at 445?

I mention this open question because I notice that you've paired with the folks at HDTT to produce a "pitch-corrected" version of this recording -- a laudable enterprise if the original is, indeed, running too fast, but an unnecessary version if it isn't. Pity HDTT didn't release an album -- simple to do with a download-only company -- offering both versions of their transfer, so that buyers could compare for themselves.

My previous skeptiucal comments on this subject were based on the running time of the 1969 first movement compared with the similar timings on Oistrakh's previous recordings. This timing of 22:35 was taken from the EMI "Great Recordings of the Century" CD release of 2003. As JM commented above, he knew that the SACD was sourced from "a PCM transfer." In the interest of using a higher-res master, I always assumed that the PCM source in question was the 24/96 transfer available at HDtracks, among others. Since, as I understood it, the GRotC series usually made 24/96 transfers and converted them to Redbook for CD release, I always assumed that the GRotC and hi-res versions were from the same remaster. My mistake! Examining the hi-res download version, I see that it came from a different transfer made in 2011. But that was only the first surprise. While the GRotC CD clearly had a timing of 22:35 for the first movement, the same track on the 24/96 had a timing of...22:23. "Triple Yikes!" as JM might say.

This, fortunately, became an easy matter to research further. Ripping the CD, and converting the 24/96 track to Redbook resolution, it was a simple task to open the two together in Audacity. And there it was...from first non-zero sample to last, the CD track had a length of approximately 22:26.261. By comparison, the 24/96 length was 22:12.200...more than fourteen seconds shorter. If that was the source used for the SACD, no wonder it would sound rushed and unnatural! (And here's the kicker: if this issue was caused by something odd in the digital transfer itself, it likely wouldn't even manifest itself as being sharp, since digital manipulation would affect the speed but not the pitch.)

The bottom line here appears to be that, all other issues from the '70s aside, there is something drastically wrong with the 2011 24/96 transfer that constitutes a significant corruption over any previous version. Unfortunately, it would appear that the current "Warner Classics" CD is likely sourced from that corrupted transfer, leaving the EMI GRotC CD as the last "official" release without this problem...glad I own a copy! (IMHO, samples I've heard of the "speed-corrected" HDTT suggest that the reel-to-reel tape used is several steps away from the master tape, with noticeable degradation of sound quality.)

I usually find track lengths to be somewhat unreliable in determining the lengths of the actual music. I always analyze the frequency content of tracks and determine the centre frequency of the "A".

Tony

...it doesn't change the fact that, when you have two transfers ostensibly from the same master tape, and the length of the music, from first note to last, on one is twelve seconds shorter than the other, it's pretty much proof-positive that at least one of those transfers has a serious flaw -- and that remains true no matter what the pitch used (as I pointed out, if the problem was in the digital transfer, the length -- and thus the apparent pace -- would be drastically different, but the pitch would be unchanged).

And note that I didn't just use "track lengths" (which can be deceptive due to extra silence at the beginning or end); I loaded both tracks into an audio editor and measured them from first non-zero sample to last, thus ensuring that any additional silence in one or the other had no bearing on the results.

Kickstart it, and let's spread the word.

Post it on the forums. 4000 records shouldn't be that big an ask?? Especially for such a legendary performance like this which will not happen again ever.