| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Lipinski Sound L-707 loudspeaker

Street buzz is a force to reckon with. When an audiophile whispers to me that a piece of new equipment sounds unusually good, I'm interested. When two manufacturers of other equipment independently tell me "You've got to listen to this speaker," I get excited.

I first heard about Lipinski Sound's L-707 loudspeaker in late December, from an engineer of solid-state equipment. Later, at the 2005 Consumer Electronics Show, a producer of high-quality SACD remasterings of classic recordings spontaneously took me by the arm and marched me over to the Lipinski Sound Corp. exhibit at the Alexis Park Hotel. What I heard there convinced me that the L-707 deserved a lengthier audition in my own listening room.

I first heard about Lipinski Sound's L-707 loudspeaker in late December, from an engineer of solid-state equipment. Later, at the 2005 Consumer Electronics Show, a producer of high-quality SACD remasterings of classic recordings spontaneously took me by the arm and marched me over to the Lipinski Sound Corp. exhibit at the Alexis Park Hotel. What I heard there convinced me that the L-707 deserved a lengthier audition in my own listening room.

Andrew Lipinski originally conceived the L-707 as a monitor to assist him in his recording of symphonic music in his native Poland. During a visit to my listening room, he mentioned several principles he'd followed in its design: Each parameter had to be optimized in an anechoic chamber; the L-707's sealed enclosure is tuned for the best impulse response rather than for deep-bass extension; its cabinet is made of 1"-thick MDF with sturdy internal bracing to damp internal resonances; the two 7" woofers have cones of stiff glass fiber with low-damping rubber surrounds, diecast chassis, and low-distortion magnets; the ring-radiator tweeter, made by Vifa, has wide dispersion and a frequency response that extends to 40kHz; while there are black cloth grilles in front of the woofers, there is no grille in front of the tweeter because Lipinski's testing suggested that any grille fabric will introduce high-frequency comb filtering; and the tweeter's Belgian foam surround was cut to fit perfectly together in layers without glue, to eliminate any "edge effect" that might color the sound.

A low-order crossover filter was chosen for the best phase response. It uses low-resistance, wooden-core foil inductors and speaker terminals of gold-plated brass that are designed to accept banana plugs or wires up to a thickness of 2 AWG. The L-707 is magnetically shielded.

To make them easier to move between recording and mixing locations, the speakers are shipped in carrying cases of rugged black nylon with side pockets, rather than in cardboard cartons.

Setup

I placed the 41-lb Lipinski L-707s on Sumiko's "Franklin and Lowell" sand-filled stands ($350/pair), which raised their tweeters 43" above the floor. Then Lipinski and his son, Lukas, placed the speakers and stands on the exact spots usually occupied by my Quad ESL-989s: 8' apart, 5' from the front wall, and 3' 9" from the sidewalls. As always, I did my listening in my lightly damped, rectangular listening room (26' long by 13' wide by 12' high). Behind my listening chair, the other end of the room opens into a 25' by 15' kitchen. All listening was done with the woofer grilles in place.

A pair of balanced interconnects ran from my Krell KCT preamplifier to the line-level right and left inputs of a Mark Levinson No.334 solid-state stereo amplifier. The phase and speaker-channel identification checks on Stereophile's first Test CD (Stereophile STPH002-2) indicated that the L-707s were in correct phase.

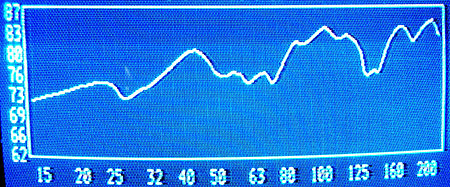

To evaluate the speaker's frequency response in my room, I used a Velodyne DD-18 subwoofer's built-in signal generator, calibration microphone, and virtual spectrum analyzer (see Stereophile, June 2004, p.133). I set up the mike on the back of my listening chair at my seated ear height of 37" above the floor and set the DD-18's volume control to "0" so that the sub would put out no audio signal. I then keyed the Velodyne's remote to display its internal System Response screen on my TV monitor. This automatically initiates a repeated sweep tone from the DD-18's signal generator, which is then fed into a tape input of my Krell KCT preamp. The L-707's frequency response showed room-mode peaks at 40Hz, 125Hz, and 180Hz, with the speaker's output falling gradually below 40Hz, to –6dB at 25Hz (fig.1).

Fig.1, Lipinski L-707, in-room response in LG's listening room

Playing pink noise from Stereophile's Test CD 2 (Stereophile STPH004-2), the L-707's tonality remained constant as I moved back and forth and side to side in my listening chair. I found the L-707s' "sweet spot" in my room to be about 12" wide and 12" deep. It was easy to stay in this sweet spot, as it was quite wide. The sweet spot dulled slightly when I stood up, but did not vary more when I moved around the room.

Sound

While the Lipinski L-707s displayed excellent imaging, extended dynamic range, and translucent mids and highs, their strongest characteristic was their wide, deep soundstage, with an unusual level of spatial resolution for individual orchestral instruments and choral voices. John Atkinson's recording of an excerpt from Elgar's The Dream of Gerontius on Test CD 2 created a wide, deep soundstage that allowed me to easily place the tenor at the far left and the brass section at the far right.

The L-707s' imaging and portrayal of space also allowed them to convey the ambience of the recording venue. Listening to the percussion solo during "Nardis," on Patricia Barber's Café Blue (CD, Premonition/Blue Note 21810 2), it was easy to locate the piano at the right, the standup string bass at the center, behind the piano, the snare at center, and the cymbals at extreme right. And when I closed my eyes, Mary Gauthier's voice singing "Long Way to Fall," from her Filth and Fire (CD, Signature Sound SIG 1273), sounded three-dimensional, actually seeming to be in the room with me.

Midrange timbres were especially rich. During "Silk Road" and "Running Water," from I Ching's Of the Marsh and the Moon (CD, Chesky WO144), I easily heard the timbres, sonorities, and resonances of Sisi Chen's yang ching (Chinese dulcimer) and Tao Chen's bamboo flute. The reediness of Antony Michaelson's clarinet was evident and highly involving during the Larghetto of Mozart's Clarinet Quintet in A Major, K.581, from Mosaic (CD, Stereophile STPH015-2). The stinging emotion and irony of Eva Cassidy's rendition of "What a Wonderful World," from her Live at Blues Alley (CD, Blixstreet G2-10046), was intensified by the L-707's ability to capture the rich tonalities and colors of her voice, which beamed with hope despite her knowledge that she had cancer (she survived the gig by only six months).

Recorded vocalists and instruments benefited the most from the L-707s' imaging and their ability to reproduce timbres free of speaker-introduced colorations. Madeleine Peyroux's wonderfully alluring interpretation, in Billie Holiday style, of Leonard Cohen's "Dance Me to the End of Love" and Hank Williams' "Lonesome Road," both on Careless Love (CD, Rounder 1161-3192-2), was never more clearly heard. The L-707s delivered a clear, undistorted image of Lyle Lovett singing "Friend of the Devil" on Deadicated: A Tribute to the Grateful Dead (CD, Arista 7822-18669-2), with no sign of the honk or chestiness that lesser speakers can inflict on male vocalists. Suzanne Vega's cover of "China Doll" on that album had all the richness of timbre I hear from this recording when I listen to it through the more expensive Quad ESL-989 and Revel Salon loudspeakers.

The Lipinski L-707's dynamics ranged wide and fast. Reproducing Eva Cassidy's cover of Simon and Garfunkel's "Bridge Over Troubled Water," also on Live at Blues Alley, the L-707 conveyed the stunning dynamic range of her voice without compression or overload. It also easily handled the wide dynamic range between drummer Mark Walker's tiny cymbal taps and his room-shaking kick-drum beats on Patricia Barber's "Nardis."

The L-707 reproduced the treble component of the musical spectrum with ease, producing extended, translucent highs. I was transfixed by the shimmer and sheen of the reverberating chimes and the reediness of the bassoon, which open Owen Reed's La Fiesta Mexicana, from Fiesta (CD, Reference RR-38CD). Bud Shank's alto sax and flute, heard on the title track of the L.A. Four's Going Home (CD, East Wind 32JD-10043), had highs that were extended, transparent, and wide open.

The L-707 reproduced the treble component of the musical spectrum with ease, producing extended, translucent highs. I was transfixed by the shimmer and sheen of the reverberating chimes and the reediness of the bassoon, which open Owen Reed's La Fiesta Mexicana, from Fiesta (CD, Reference RR-38CD). Bud Shank's alto sax and flute, heard on the title track of the L.A. Four's Going Home (CD, East Wind 32JD-10043), had highs that were extended, transparent, and wide open.

Bass notes were reproduced with power and good pitch distortion, despite the fact that the two-way L-707 has only two 7" mid-woofers to handle the bass and midbass. The Lipinskis allowed me to enjoy pedal notes from the pipe organ on "Lord, Make Me an Instrument of Thy Peace" and "A Gaelic Blessing," both from John Rutter's Requiem (CD, Reference RR-57CD). The blend of synthesizer, Tibetan horns, and monks of the Gyuto and Drukpa orders chanting on "Sand Mandala" and "Caravan Moves Out," from Philip Glass's soundtrack for the film Kundun (CD, Nonesuch 79460-2), produced deep bass, exotic sonorities, and droning chants that were oppressive, anxiety-provoking, and highly dramatic. Solid, deep organ-pedal chords resonated in my room as I listened to Jean Guillou perform Gnomus, from his transcription of Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition (CD, Dorian DOR-90117). Though Tuileries, from the same disc, didn't rattle objects or cause the air to pulse as it does when I play it through large subwoofers, it still thundered and growled through the L-707s. And the large bass drum and synthesizer on I Ching's Of the Marsh and the Moon gave a solid, tuneful foundation to "Silk Road" and "Running Water."

It was a special pleasure to hear Lipinski's own recording of Krzysztof Penderecki's Clarinet Concerto (CD, Koch 521102) in my listening room. Lipinski was the sole engineer for this recording, and used L-707s as monitors while editing the release, so it was no surprise that the L-707s beautifully reproduced the complex orchestral timbres, instrumental placement, and wide dynamic range of this work. Clarinetist Dimitri Ashkenazy played with energy, technical skill, and superb tone as captured by the L-707s, which placed him in a wide, deep soundstage. I found myself closing my eyes and luxuriating in the clarinet's richness and warmth, so ably reproduced by the Lipinskis.

Conclusions

The buzz on the street is correct. Andrew Lipinski has designed and manufactured a portable monitor loudspeaker with many of the high-end qualities—great dynamic range, detail, pace, three-dimensionality, imaging, and the ability to accurately reproduce instrumental and vocal timbres—that I usually associate with expensive audiophile loudspeakers. While it doesn't reach all the way to the bottom, its depictions of drums and pipe-organ pedal notes have good pitch definition and ample weight to convey the drama of those instruments. The L-707 is better at involving the listener in the drama of music than it has any right to be at its price of $4590/pair. Be assured that its quality grows even more with exposure. This loudspeaker wins my recommendation for inclusion in the "Class A (Restricted Extreme Low Frequency)" category of Stereophile's "Recommended Components."

- Log in or register to post comments