| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

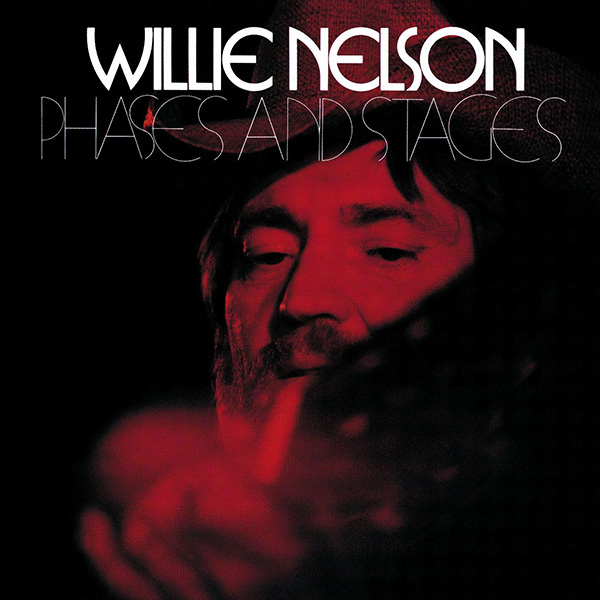

I will join in loving Willie, Merle, and more. (But stop shit talking Lyle, he's fine, too.)

If vinyl lovers are interested, VMP made a great set, and included a fantastic Nelson gem album "Across the Borderline," a sublime Willie covers album that is demo quality Hi Fi, as well.

https://www.vinylmeplease.com/products/the-story-of-willie-nelson?variant=39827700252762

I certainly concur with you about their greatness, and about their relative lack of being better appreciated.

Wynton Marsalis made a great quip once: As jazz and country music became established, the main difference was that jazz leaned toward brass instruments and country more toward stringed. (There are bountiful exceptions, of course, but I appreciated his take.)

_

Many audiophiles in America came of age during the time of that abominable "countrypolitan" music, which was the rhinestone leisure suit, syrupy orchestra, and forced duet era; so, you have to cut us some slack!