| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

something to the effect that it was nice to once again be on good terms with the magazine. Anyone care to fill in the details? I don't remember anything but very positive reviews as to every VPI table ever reviewed.

VPI includes a palm-sized tracking force gauge, but it fell apart when I tried to use it. I used my Riverstone Audio Precision Record-Level Turntable Stylus Tracking Force Gauge/Scale to set the Ortofon Verismo cartridge to the specified tracking force of 2.8gm. VPI's metal alignment jig fits between the spindle and tonearm-bearing base, making it easy to align the cart with a single null point, which I then confirmed with my Dr. Feickert Analogue Universal Alignment Protractor. I checked platter speed with the RPM app on my iPhone: a steady 33.45rpm. Azimuth is preset, but it required minor adjustment to be perfect.

Harry Weisfeld believes his FatBoy arm sounds better with no antiskate. I found that to be true—when the cartridge wasn't skipping. Without the antiskate, the Verismo seemed to skip on the smallest speck of dust. So, I looped the plastic wire extending from the tonearm base over a metal peg on the small, V-shaped antiskate mechanism attached to the back of the VTA tower. After that, no more skips.

Listening and listening more

My role as a Stereophile scribe requires me to expound on the equipment under review. My job is to explain, describe, and clarify the qualities that determine the personality of, in this case, a turntable/tonearm/cartridge combination.

I cringe at putting myself front and center—always have—but it's necessary here, in this review, as the VPI Avenger Direct helped stir sensations I've not often felt while performing an equipment review.

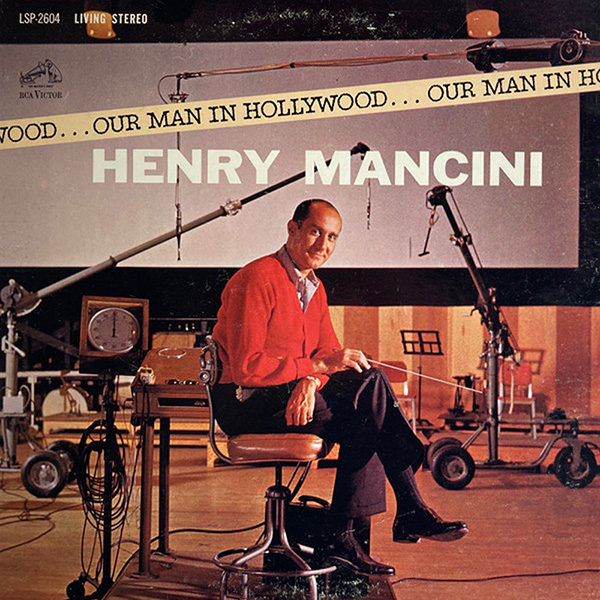

After I lowered the Verismo stylus into the run-in groove of Al Schmitt's 1963 production of Henry Mancini's "The Days of Wine and Roses" (from Our Man in Hollywood, RCA Living Stereo LSP-2604) and started walking back to my chair, a French horn threw the song at me, as if I were waking from a dream.

"The Days of Wine and Roses" is a powerful song, a bittersweet Mancini/Mercer collaboration. The performance by Mancini, the Mancini Chorus, and a crack LA orchestra is masterful.

Mancini's surging strings swelled, spiraled, crawled up my back, over my shoulders, and down my chest. I was surrounded by music, engulfed. I felt lightheaded, disembodied, at one with the music, in some kind of head-trip nirvana. I felt the recording's low end in my legs. I grabbed a beam to steady myself. It felt like I was levitating. This was senses-quivering emotional overload.

This was a rare instance in which my logical left brain was overpowered by endorphins and right-brain passions. I was (momentarily) free of such reviewer's concerns as bass extension, midrange transparency, imaging, and the like. I seemed to disappear. The music filled the space that was previously me until song's end. The VPI vanished, too, leaving only music.

The Avenger Direct mined all the musical detail, dimensionality, ambience, and opulence of the Mancini recording, but more importantly, it mined its emotions.

I admit to some preconditioning. For years, this soundtrack has pounded me with its music and its melancholy message, and I've long been affected by it. What's more, I have experienced something similar—a similar emotive grip—occasionally, as when my soul got caught up in The Beach Boys' seismic "'Til I Die" (Surf's Up, Reprise Records RS 6453), Russian composer Vasily Kalinnikov's Symphony No.1 (His Master's Voice ASD 3502, Melodiya ASD 3502), Miles Davis and Bill Evans's "Blue in Green" (Kind of Blue, Columbia CL 1355), and Lizz Wright's reading of Gordon Jenkins's forlorn "Goodbye" (from Salt, Verve Records 589 933-2).

This total emotional immersion did not, of course, occur with every record—but musical immersion did occur, LP after LP. The VPI played vinyl with physicality and illuminating dynamics, reproducing increments of emotion that make a musician or vocalist appear whole in your listening room, fully real, organic though also hyperreal. This enhanced realism—this ultrareality—was consistent regardless of amplification or speakers.

On the Great Jazz Trio's Milestones (Inner City Records IC 6030), Tony Williams's drums had never sounded so alive and whole; each cymbal crash and tom punched through me like a scorching flash of heat. The Verismo cart was focused and blue-sky clear, its midrange possessing nuanced textural shading. The Avenger Direct let the Verismo dance, sing, breathe, while presenting levels of physicality and texture that aided my capacity to experience the music as practically a live event.

Years spent playing drums in jazz ensembles and commercial pop bands have trained my soul and ears to recognize the sound of instruments vibrating in ambient space. With the VPI/Ortofon/Manley trio, music blossomed well beyond a flat plane, flowing from the DeVore O/96 speakers into a pressurized space where the studio walls were practically there, establishing a sense of musicians performing in space and time. I attended the music as a slack-jawed bystander, witnessing recorded history like some sonic time-tourist.

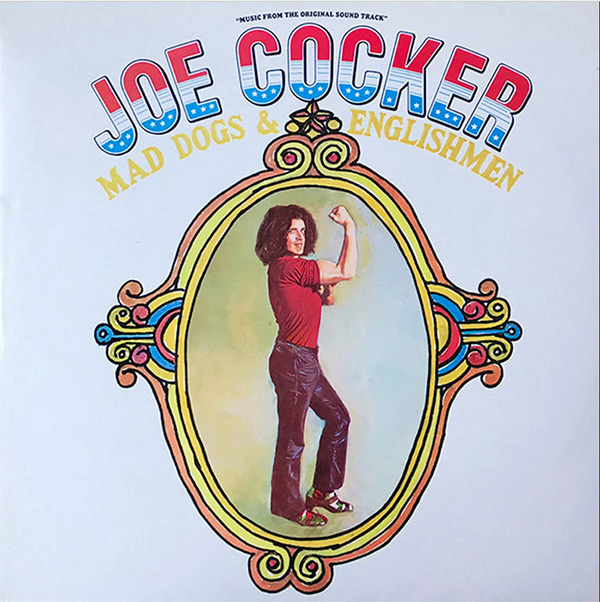

A similar elevated sensory experience occurred when I played Joe Cocker's Mad Dogs & Englishmen (A&M Records SP-6002). This 1970 live-from–Fillmore East double album features Cocker fronting a Leon Russell–led rock'n'roll big band, performing covers of Rolling Stones, Traffic, The Beatles, Sam & Dave, and Otis Redding. Mad Dogs is a classic rock and roll document. The VPI/Verismo duo placed me first row at Fillmore East, the ballsy sounds of vocalists Claudia Lennear and Rita Coolidge soaring above. Cocker's sweat and spittle pelted me. The VPI replicated the kinetic energy, drama, and scale of the Mad Dogs' performance.

The VPI/Verismo sound was all about force and subtlety, finesse and speed. Bass was taut on a soundstage worthy of gladiators, a large, musician-haunted diorama. Part of what made every recording brilliantly alive was the dead silence the duo produced when the music wasn't playing. As I write this, though, I can't help feeling it's cheap to reduce the VPI's performance to separate traits when its great strength is its presentation of such a unified, stirring whole.

If memory serves, the gargantuan scale and spirit of the VPI presentation was similar to that of the Clearaudio Reference Jubilee, with perhaps more physicality and drive. My Kuzma Stabi R turntable (with Clearaudio Jubilee Panzerholz MC cart) is powerful and sounds immense, yet it lacks the openness and exhilaration of the VPI/Verismo combo; it is, however, perhaps more sensual. The Clearaudio Jubilee is a beauty and grace machine; the Kuzma Stabi R has a darker presence, possessing a more serious mien. But wouldn't you know it? For drive and punch, none of these 'tables matches my Thorens TD 124. Idler drives rule!

Meet Shyla

Where the Ortofon Verismo MC cartridge played music with elegance, ecstatic physicality, and surgical detail, the VPI Shyla featured juicy tonality, exciting speed, and viscosity that made instruments and vocals tactile, clothed in resplendent colors and rich tone.

Summing up

I'd heard the Avenger Direct at Capital Audiofest in VPI's room, where Harry was using Ed Graham's Hot Stix (M & K Realtime Records RT-106) as a dynamics torture test. It's one thing to be impressed by a component in an unfamiliar system at a noisy, hectic hi-fi show; it's another to listen in your own home, on your own system, playing your own favorite records. I can't credit the VPI entirely with the ecstatic experience that resulted; for one thing, the Verismo was important—a great match. The rest of the system contributed, too (not to mention the music), and apparently, I was in a receptive state, for whatever reason. Still, transcendence is what many of us seek from music, and the VPI Avenger Direct, with help, delivered it.

Beyond that transcendent moment, in my walk-up crib, the Avenger Direct recast records I thought I knew well, unmasking secrets and expressing a purer sense of each one's interior life. It vanquished time and space, placing me at studios in Hackensack, Englewood Cliffs, Abbey Road, and Oslo, and at various concert halls. It made new music from old records and gave me greater respect, even awe, for the musicians who played it and the analog time machines that play it back.

Harry tells the story of when he and Mat visited the great Illinois Jacquet at the saxophonist's New Jersey home in 1996. Mat, who was 13 at the time, began playing Jacquet's piano. "Illinois comes over to me and says, 'Never let that boy stop,'" Harry recalled. "'Let the boy keep playing!'"

I don't know what deed this Avenger is meant to avenge, but its place in the pantheon of great turntables is secure.

something to the effect that it was nice to once again be on good terms with the magazine. Anyone care to fill in the details? I don't remember anything but very positive reviews as to every VPI table ever reviewed.

and brutally honest take down of that short lived, poorly engineered Shinola turntable that was made by VPI? Or did I miss another review of a VPI product? If I recall, Fremer raved about their top of the line direct drive tt so who knows? Could be many things.

Not sure about where the review is but that was a learning experience in working with a lifestyle company. They had the right goals and ideas... and I'll leave it at that. Either way, that table had its day, and when it ran its course everyone moved on in their own direction.

There were some miscommunications that initially led to some frustrations. Sitting down, talking, and listening to music led to everyone getting on the same page :)

Hey Mat-

Good to see you chime in; maybe you can clear up another miscommunication?

The review said the following:

In its earlier implementation, the motor was driven as a brushless, direct-current (BLDC) motor; in the later direct-drive 'tables, including the Avenger Direct, it is implemented as a PMAC (permanent-magnet AC) motor, "driven sinusoidally as a three-phase AC motor," Harry wrote in an email.

The HW40 used a controller from Elmo Motion Control (Gold Solo Twitter series) and did not drive the motor as a PMAC type, it used block commutation not sinewave drive. The review goes on to say the Avenger Direct uses a TI controller. So, did you change the controller between the HW40 and the Avenger Direct or does it use the same Elmo controller and block commutation? The quote above would imply that only the Classic Direct (ca 2013) used BLDC drive and newer tables (including the HW40) used sinewave drive, which the HW40 clearly does not. I confirmed with Elmo MC via e-mail in 2019 that the Gold Solo Twitter is not capable of sinewave drive or FOC. Can you please clarify.

If there is a new controller, is there an upgrade path for the HW40 users?

The torque spec they publish is somewhat dubious and contains the same typo as the HW40 (torque units are Nm not Nm/sec). The ThinGap TG231 motor is capable of 2.68Nm of torque for 1 second max and it takes 40A at 12V (~500W) to achieve this. On the HW40, this was limited to .74Nm at start up by the 50W power supply (and in software) and the torque during normal operation was 0.0068Nm, about the same as most modern belt drives. Not sure why they chose a 500W motor to drive a platter that requires ~30mW during normal operation.

It's interesting that they changed the drive electronics but kept the same magnetic ring encoder. The HW40 used an off-the-shelf industrial controller from Elmo Motion Control (Gold Solo Twitter) and employed block commutation which can produce torque ripple (cogging). It was also quite noisy electrically, producing 36VPP squarewaves at 10kHz with no filtering (class D output, I could actually hear a high pitched whine at start up). The TI controller should be better with sinewave drive (hopefully they got rid of the class D output stage).

The RLS magnetic ring encoder produces 80 pulses per rev for speed control, but the read head can synthesize 32 counts out for each input pulse producing the 2560 PPR they claim. The HW40 measured the speed once per second so the count for 33.333 RPM was non-integer (2560/1.8Sec=1422.222 counts/sec) and the speed was always going between 33.351 (1423) and 33.328 (1422) on the unit I looked at. Hopefully, the TI controller uses a different time window or can work with fractional counts.

I wonder if the early adopters of the HW40 will have an upgrade path to the new controller?