| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

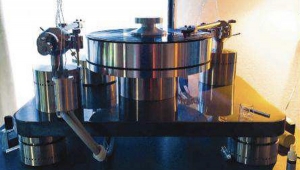

Analog Corner #250: Ikeda 9mono, van den Hul Crimson XGW cartridges, PBN GrooveMaster Vintage Direct turntable

The review gear piles up, and it's time for a late spring cleaning—not that any dust has gathered on the uniformly excellent products covered in this column. I'll start with two very different phono cartridges.

Footnote 1: Ikeda Sound Labs, Japan. Web: www.islabs.co.jp. US distributor: Aaudio Imports, 4871 Raintree Drive, Parker, CO 80134. Tel: (303) 264-8831. Web: www.aaudioimports.com,

Ikeda Sound Labs 9mono moving-coil cartridge: $4400

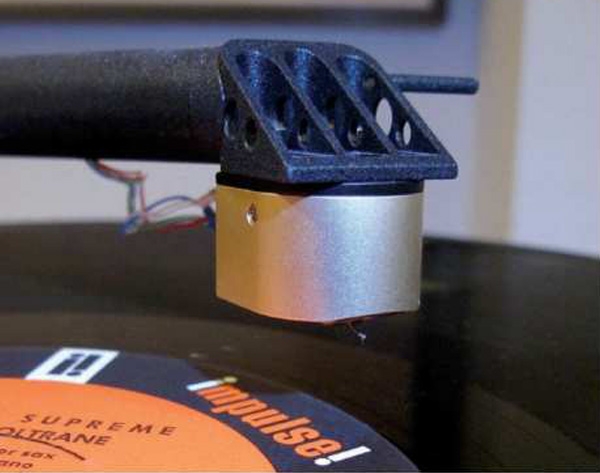

The Ikeda Sound Labs 9mono cartridge ($4400, above; footnote 1) is a dedicated mono design intended to integrate well into a modern stereo system. Within its curved body, made of solid aluminum alloy, is a low-output (0.22mV) moving-coil motor with a very low internal impedance (2.0 ohms). Generally, both specs mean fewer coil windings and low moving mass. And lower mass usually means fast response and excellent detail retrieval.

The 9mono's specified vertical tracking force (VTF) is 1.8gm, ±0.2gm. Its cantilever is a double-layer duralumin pipe, to which is fastened an "oval-shaped"—presumably elliptical—solid diamond of unspecified dimensions. The 9mono weighs 10gm, and its compliance is suitably low, at 7x10–6 cm/dyne.

Ikeda claims that they chose the 9mono's stylus shape and dimensions to ensure compatibility with mono records pressed "in every period." Original mono LPs (beginning in 1948) were cut for a stylus with a radius of 1 mil; newer ones (say, from the mid-1960s forward) were cut for a 0.7-mil stylus—and, of course, many of the mono LPs being pressed today are made with a stereo cutter head and cutting stylus.

The advantage of a playback stylus with an elliptical profile—eg, 0.3 by 0.7 mil—is that it will ride in the groove at the same height as a conical 0.7 mil stylus, but its 0.3 side profile will do a much better job of tracing high-frequency groove modulations—especially as the groove nears the label—than will a conical stylus. The fact remains that no stylus profile is optimal for all mono records, but that is more an archivist's problem than one we in the playback world need worry about.

Ikeda says that, rather than modifying a stereo model, they developed the 9mono as a mono cartridge from the ground up. However, the 9mono does have two fully independent coils, wound vertically to produce output only from horizontal movements of the stylus. When used in a stereo system, this dual-coil design is said to avoid the hum problems produced by some other mono cartridges. I didn't experience any hum problems with the 9mono.

If you have only stereo LPs, or have only a few monos that you rarely play because you hate mono, you don't need a mono cartridge. But in the past decade or so, more vinyl fans have realized that many so-called "stereo" records cut from master tapes produced in the 1960s and recorded on four-track tape decks were actually panned mono with added reverb, and that these "stereo" versions were after-the-fact mixes, often produced anonymously, following the completion of the more important mono mix, in which the artists usually participated.

That was true of the Beatles, of course, and of Bob Dylan, who stayed in Nashville for the mono mix of Blonde on Blonde, then split, leaving the stereo mix to others. This was early 1966, and he figured that most of his fans were still listening in mono. He was correct.

The advantage of a dedicated mono cartridge is that it ignores the vertical modulations caused by record warps, which produce only rumble and noise. The elimination of rumble is important, but so is a mono cartridge's ability to ignore many scratches and, depending on how an older record has been played, wear.

I once bought for a dollar, at a church rummage sale, an original pressing of Philles Records Presents Today's Hits (LP, Philles LP 4004), a compilation of producer Phil Spector's greatest up to that point. It looked trashed—but when I played it using a mono cartridge, it sounded in near-mint condition, with just barely audible noise between tracks. The same was true of a few mono Rolling Stones LPs on London Records. They looked awful; they sounded nearly perfect. Often, their visibly worn condition means you can pick up such valuable records for next to nothing—yet they can play as new.

If your tonearm allows for easy headshell or armtube swapping, you're all set: alternating between stereo and mono cartridges will be a cinch. Otherwise you'll have to invest in a second tonearm, assuming your turntable can handle two arms—or you can replace your original arm with one that's more accommodating.

And if your electronics include a mono switch, you're in luck. Flipping it when playing a mono record with a stereo cartridge will electronically cancel out rumble produced by vertical groove modulations. While that makes mono records sound better, a mono cartridge considerably improves the results.

Sound: The vinyl-and-SACD label Analog Spark has released an astonishing-sounding reissue of the Original Broadway Cast recording of Lerner and Lowe's My Fair Lady (Columbia OL 5090/Analog Spark 88875107331), mastered by Ryan K. Smith from the original 1956 master tape (footnote 2). I played it first using a stereo cartridge—with my darTZeel NHB-18NS preamp's Mono switch flipped—and then I played the LP with the Ikeda 9mono.

Leaving aside the audible differences between the cartridges, the 9mono produced a tighter, better-focused, totally stable image between the speakers. This has long been my experience when comparing the playback of a mono LP by a stereo cartridge (with a preamp's Mono switch engaged) and that same LP played by a mono cartridge. I heard a similar difference between mono and stereo cutter heads a few years ago, when I visited the Electric Recording Company, in the UK.

The Ikeda 9mono's transient performance was on the smooth and polite side, bordering on soft but not quite soft. This was more than compensated for by its impressive transparency and tonal neutrality, plus its especially fine rendering of stage depth. If you don't think mono can do depth, listen to "Wouldn't It Be Loverly" from this record through the 9mono!

However, there was a bit less air and transient snap than I'd heard from this reissue through other cartridges, including the Miyajima Labs Zero, so I played some other familiar mono LPs. Same story: The 9mono delivered the detail, but wrapped it in a pleasingly satiny finish. This was with the cartridge's loading set to around 44 ohms. Raising the loading didn't change the satiny finish, but it did add the expected high-frequency glare.

The Ikeda 9mono's smooth, burnished overall sound will appeal to those who like the My Sonic Lab and Air Tight cartridges built by Y. Matsudaira, or who think Lyra's Olympos was that brand's pinnacle. I most enjoyed the 9mono's stable, well-organized sound, tonal neutrality, and transparency. Overall, its sound was a bit too smooth for me, but that's just me.

On the other hand, when I played the Electric Recording Company's reissue of János Starker's first recording of J.S. Bach's Six Suites for Unaccompanied Cello, originally released by EMI between 1958 and 1961 (3 LPs, EMI/ERC 33CX 1515/1656/1745), it turned into an all-evening recital ending in complete satiny satisfaction!

van den Hul Crimson XGW moving-coil cartridge: $4994.99

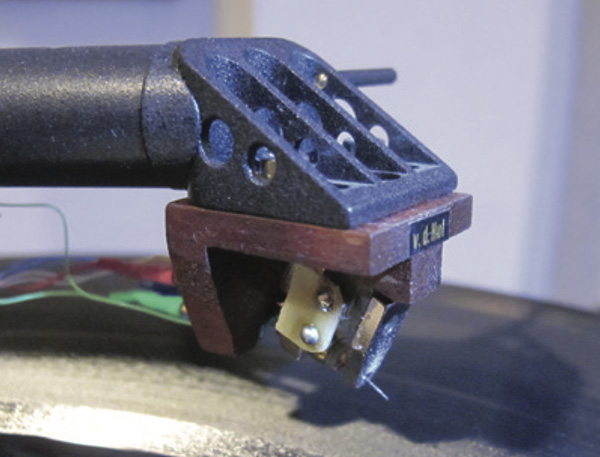

Analog pioneer A.J. van den Hul has been designing and building high-performance phono cartridges for more than 30 years. He began as an audio reviewer, and from there got into the retipping business. His first major innovation was an extreme stylus profile still used today—including in the surprisingly sweet-sounding van den Hul Crimson XGW (footnote 3).

With its 0.08 by 3.5 mil stylus—the latter number sounds yuuuge, but as with all such specs, that's the radius of the curve of its front, not its dimension—the Crimson XGW's van den Hul 1S stylus profile can get into every nook and cranny of the groove. Thus it can extract maximal high-frequency detail, even from the part of the groove closest to the record label, where the small groove radii scrunch up the waveforms. When introduced, the 1S profile caused concern among some vinyl lovers, who worried that its sharp edge would result in more groove slicing than groove tracing. But those fears proved unfounded, at least with careful setup.

Like the van den Hul Crimson XGA (amber) and the Crimson XGP (polycarbonate), the Crimson XGW (wood) is a nude design: its exposed motor is attached to a specially lacquered body of koa wood, and there is no stylus guard. That's something to be carefully considered by cat owners, klutzes, and people fortunate enough to have a cleaning person, because there's no way to protect the stylus from them—or from you—and that complicates initial setup. I can tell you that, at the end of each listening session, before heading upstairs, I'm in the habit of replacing the stylus guards on each of my cartridges.

With its unusually high output of 0.9mV, it's not surprising that the Crimson's internal resistance is 13 ohms, which means a healthy number of turns of 24K gold wire. vdH recommends loading the cartridge at a value from 25 to 200 ohms.

The 1S stylus is attached to a boron cantilever. The XGW's channel separation is specified as ">36/30dB," its static compliance as 35µm/mN. You'd halve that figure for the dynamic compliance (unspecified), which makes sense, given that the effective tonearm mass suggested for the XGW is 10–16gm: add the XGW's mass of 8.75gm and, were that high compliance spec applicable to dynamic conditions, you'd need a low-mass tonearm in order to achieve the desired resonant frequency of 8–12Hz.

I used the Crimson XGW in the Kuzma 4Point tonearm, which has an effective mass of 14gm. The cartridge tracks at a light 1.35–1.5gm. Setup was relatively easy, thanks to the XGW's high build quality. With the arm parallel to the record surface, the stylus rake angle (SRA) was very close to 92°, and with the cantilever perpendicular to the record surface, the XGW achieved nearly ideal channel separation: +30dB in both directions, and balance within 1dB. I'd rather achieve better channel balance between the channels than maximize the separation in one direction, which is also achievable.

Footnote 1: Ikeda Sound Labs, Japan. Web: www.islabs.co.jp. US distributor: Aaudio Imports, 4871 Raintree Drive, Parker, CO 80134. Tel: (303) 264-8831. Web: www.aaudioimports.com,

Footnote 2: See my interview with Ryan K. Smith.

Footnote 3: A.J. van den Hul, The Netherlands. web: www.vandenhul.com. US distributor (2024): VPI Industries, 77 Cliffwood Ave W #5D, Cliffwood, NJ 07721, Tel: (732) 583-6895. Web: www.vpiindustries.com.

- Log in or register to post comments