| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Analog Corner #254: Audio-Technica AT-ART1000 phono cartridge

Recently, after 36 years at Audio-Technica, Mitsuo Miyata retired—by which time he'd run out of business cards. Nonetheless, when I met him in early July at A-T's headquarters, in Machida, Japan, he handed me a card. A line had been drawn through the original cardholder's name; under it, handwritten, was Miyata's name.

Footnote 1: See my interview with Mitsuo Miyata here.

Japanese culture is so formal that there is a precise etiquette of how to offer one's business card: Hold the card lengthwise in both hands, gripping it between thumbs and index fingers, and present it with a slight bow. For someone with so long and distinguished a career and multiple patents to his name, Miyata's offering was casual. Later, an A-T staffer told me, with a laugh, that he'd never before seen Miyata in a tie and jacket, both of which he wore for our meeting.

Today, the inventor of Audio-Technica's new AT-ART1000 cartridge is better known around company headquarters as a gentleman farmer—a grower of legendary blueberries, Japanese eggplants, and corn. His home-built stereo system is also said to be pretty special. I had been invited to meet him, and to get an exclusive look at the challenges of assembling and testing the AT-ART1000.

In the early 1990s, when Audio-Technica's cartridge business began to taper off, Mitsuo Miyata (above) turned his attention to the mechanical design of headphones. His various patents relate to the physical, not the electromechanical aspects of headphones. Today, A-T is the best-selling headphone brand in Japan, and half of the company's business is headphone related. Another quarter of total revenues are made from the sales of consumer and professional microphones. A wall at A-T HQ displays gold and platinum albums, showcasing recordings where Audio-Technica microphones were used for such artists as Elton John, Barbra Streisand, and Tony Bennett.

Audio-Technica was founded in 1962 by the late Hideo Matsushita, to manufacture phono cartridges. The company is now run by Matsushita's son Kazuo; their line of cartridges remains extensive, their enthusiasm for and investment in analog strong. Still, cartridge revenues are so small that they don't even appear as a separate category in the company's pie chart of sales. Instead, cartridge sales are included in the broad category of "AV Accessories," which accounts for 9.9% of A-T's revenues. In fact, when vinyl's future seemed bleakest, Audio-Technica even began manufacturing automatic rice-ball-forming machines, for use in making sushi at home or in restaurants—still a successful product line.

But through all of turmoil of shifting formats, Audio-Technica continued to come up with innovations in analog playback, and with retirement on the horizon, Miyata set his sights on fulfilling one last dream: designing a Direct Power System moving-coil phono cartridge that would be reliable and reasonably practical to manufacture. In a Direct Power System cartridge, the coils and magnet system are placed directly above the stylus instead of inside the cartridge's body, behind the cantilever's fulcrum.

Miyata brought to our meeting a box containing various iterations of his concept, which he's been developing for decades. During the interview (footnote 1) he acknowledged both the original 1962 George Neumann DST 62 version of the idea, and JVC's MC-1, introduced in in the late 1970s or early '80s (I couldn't find the exact release date). In fact, in a patent application filed December 3, 2015, Miyata described the other designs in great detail, and explained why his differed enough from them to deserve a patent (footnote 2). The application goes into detail about the issues related to the Neumann's triangular air coil and the JVC's octagonal "printed" air coils, as well as about how his own design improves on those designs and solves some of their problems.

Be sure to read, in Art Dudley's review of Tzar Audiology's Tzar DST cartridge ($10,000)—essentially, a reinvention of the original Neumann design—his excellent descriptions of the advantages of placing the coils directly atop the stylus, and of why all of the "normal" cartridges we know and love operate under compromised conditions. Tzar importer Robin Wyatt, of Robyatt Audio, had first sent the Tzar to me for review. But between the Tzar's spherical stylus, ultra-high mass, and ultra-low compliance, requiring a vertical tracking force (VTF) of 3.2–4gm—not to mention problems with hum—I chose to pass on it. "Not for me; more for Art," I told Wyatt. I'm far less interested than Art is in exotics like the Tzar DST—or, for that matter, vintage gear in general.

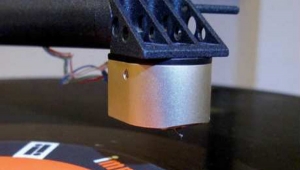

The AT-ART1000

The least expensive cartridges in Audio-Technica's extensive line (footnote 3) are made in China, at a factory owned by A-T. The company's facility in Fukui, Japan, established in the early 1970s, produces the more expensive models. The AT-ART1000, however, is built in a small corner of a large, multistory factory in Machida that mostly builds professional and consumer microphones and some headphone parts.

To manufacture Mitsuo Miyata's design—I was able to watch but not film the process—eight turns of ultrathin (20µm diameter), enamel-coated, Pure Copper Ohno Continuous Cast (PCOCC) wire are hand-wound on a bobbin using a miniature coil-winder; the result is a nonmagnetic, air-core coil with an inner diameter of 0.9mm. A coil with a ferrous core produces greater output, but it's heavier, and has hysteresis and other problems that air-core coils don't. (Its lower output is an air coil's main disadvantage.)

A tiny drop of alcohol is then applied to the wound coil. The alcohol melts the wire's enamel coating, which coats the entire assembly and then resolidifies, leaving a physically stable, perfectly round coil that can be removed from the bobbin without deformation.

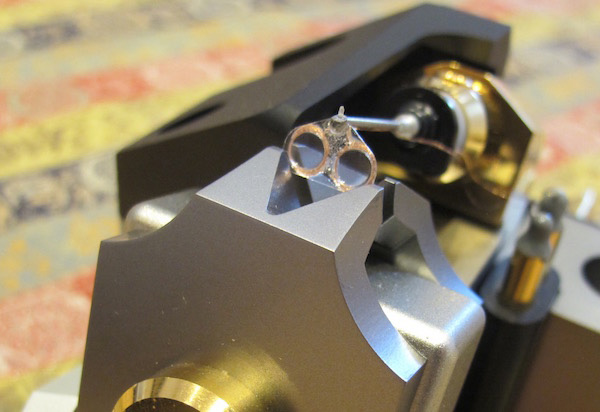

The AT-ART1000 builder uses the coil-winder to produce these tiny coils in pairs, carefully dressing the long ends of the coil wires. She then carefully places under her microscope a tiny, stiff piece of transparent film into which have been manufactured ("not machined," I was told, though I was not told how it was made or by whom, both of which remain top secret) circular grooves angled at 45°/45°, and straight pathway grooves for the coil leads.

The builder must then precisely maneuver the coils into the circular grooves. There is no margin for error. Once the coils are in place, she then adds a special adhesive, which affixes the coils to the film. If one coil moves before it's adhered to the film, the whole thing has to be tossed out and she must start over again.

Once the manufacture of the film/coil assembly is complete, it goes into a special jig, after which an assembly comprising a 0.26mm-thick solid boron cantilever and a 1.6µm x 0.3µm fine-line-contact stylus (this looks similar but not identical to what Lyra uses in its Etna and Atlas cartridges) is carefully placed atop the film, stylus pointing up, the stylus shank's top cradled in a notch in the film.

The builder then very carefully applies a small amount of adhesive (probably an epoxy-based resin) to affix the stylus shank's crown to the film. The angle then formed by the film-and-coil assembly and the stylus must be spot on, or the coils will not sit centered in the magnetic gap of the neodymium magnet directly above. Nor is there any room for azimuth error in the placement of the stylus shank in the film groove, or the entire coil assembly will be lopsided in the gap.

Next, this assemblage goes into another custom-designed (by Miyata) jig that places the rear end of the cantilever into the stopper pipe, which is then affixed with a tiny grub screw as the multilayer circular damper is pressed into place on the cantilever.

Then comes the task of dressing, flattening, and affixing the tiny coil wires to the top of the cantilever—not easy. That done, the stopper pipe is mounted on a fixture attached at the back of the cartridge's titanium body. Finally, the thin coil wires are attached to terminal posts, two on either side of the cantilever assembly.

That's all there is to it!

Every one of these tasks is performed by one specially trained, steady-handed, even-tempered young woman who knows that if, at any point, she makes just one mistake, she must chuck everything she's done and start over. All of which explains why Audio-Technica says it can annually produce a maximum of 200 AT-ART1000s for $5000 apiece.

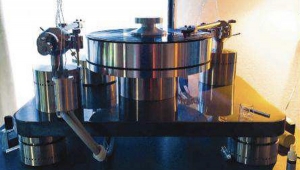

After assembly, each cartridge is put on a high-quality direct-drive turntable and measured to ensure that it meets the model's published specifications. However, the AT-ART1000's unique architecture means that each unit produced has a specified VTF, and not, as usual, a suggested range within which you can choose the setting that sounds best to you. My review sample's VTF was specced at 2.5gm. Specifications common to all AT-ART1000s include: a frequency range of 15Hz–30kHz, output voltage of 0.2mV (1kHz, 5cm/s), channel separation of 30dB (1kHz), channel balance of 0.5dB (1kHz), coil impedance of 3 ohms (1kHz), load impedance of <30 ohms (when used with head amp), coil inductance of <1µH (1kHz), static compliance of 30 × 10–6cm/dyne, dynamic compliance of 12 × 10–6cm/dyne (100Hz), and a mass of 11gm.

In other words, while this design is unique and evolutionary (revolutionary in the experience of most of us), its electrical and physical characteristics are typical of very-low-output MC cartridges. If you read the patent application, you'll understand how Miyata accomplished this.

A caveat: Because of the complexity of this labor-intensive, handbuilt design, a rebuild will cost about 65% of the cartridge's original price, or ca $3250. No matter how good it sounded, this is not a product I would buy from any company other than one as stable and long-lived as Audio-Technica.

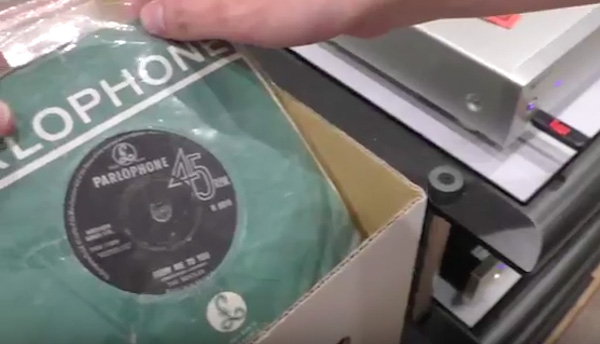

Now that its designer has retired, you may wonder who has taken over the production of the AT-ART1000. That would be Yosuke Koizumi, chief engineer for cartridge design, who's been with Audio-Technica since 2002, and who looks to me far younger than his 36 years. To assure me that a genuine vinyl enthusiast was in charge, on the second day of my visit Koizumi brought to the factory part of his extensive collection of 45rpm pressings (footnote 4). Despite the enormous gap in our ages, our musical tastes are very similar! He played for me a live Move EP I'd never heard or even seen. Envy reigned. The A-T factory's collection of LPs is also quite good, combining new and vintage high-quality pressings of musically excellent jazz, rock, and classical recordings.

Audio-Technica's listening room was also impressive. The room is acoustically well designed and treated, and on my visit contained good gear: big Pass Labs monoblocks driving Bowers & Wilkins 802 speakers. They didn't want me to take pictures of the system's front end, so I won't mention brands—but it was equally good. I left Japan impressed by what I'd seen and heard (footnote 5).

Footnote 1: See my interview with Mitsuo Miyata here.

Footnote 2: The patent can be read at http://patents.justia.com/patent/20160192080.

Footnote 3: Audio-Technica U.S., Inc. 1221 Commerce Drive, Stow, OH 44224. Tel: (330) 686-2600. Web: www.audio-technica.com

Footnote 4: Virtually browse Koizumi's singles collection here.

Footnote 5: Take a virtual tour of A-T's headquarters (unfortunately, the factory was off-limits to photography) here.

- Log in or register to post comments