| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Cosimo Matassa, laissez les bon temps rouler in New Orleans

It's no secret that the musical history of New Orleans is rich and varied. From Buddy Bolden to a young Louis Armstrong being consigned to the Colored Waif 's Home for shooting off his stepfather's pistol on New Year's Eve, to the many pianists who accompanied the irresistible allure of Storyville, musicians and their music have forever been a key ingredient in NOLA's flamboyant DNA. Most elemental of all—did he facilitate the birth of rock'n'roll?—are those honeyed days at Cosimo Matassa's humble but groundbreaking studio J&M Recording on Rampart Street (1947–1956). There, his infallible ears and uncanny skill placing microphones somehow imparted a raw and very real sound to early recordings of Roy Brown, Little Richard, Fats Domino, Dave Bartholomew, Ray Charles, and my personal favorite, Smiley Lewis. Such labels as Atlantic, Mercury, Aladdin, Specialty, Chess, Savoy, and Modern sent artists to The Crescent City, hoping to glean some of Matassa's elusive magic.

About his methods, Matassa, one of the seminal figures of popular recorded music, once told WWOZ radio (wwoz.org), the tenacious cheerleader of NOLA music history, that "The first thing we had was a dual Presto disc recorder. It was called a 28N—two Presto 8N recorders," Matassa said. "There was no intercutting, no tape editing. In fact, those were the good performances, probably some of the best because they were really performances as opposed to the synthesized [recordings] you make today. If you listen to the way the drums sound on the very earliest things, you can tell they were done on one microphone. ... On some of those early things, that the records sounded decent at all by today's standards is a miracle."

In Matassa's 2019 obituary on NOLA.com, the great Allen Toussaint observed, "Cosimo was the doorway and window to the world for us musicians in New Orleans. An expert, with a lot of heart and soul. When the Beatles heard Fats Domino, they heard him via Cosimo Matassa. He touched the whole world."

While New Orleans music has an unquestionably glorious past, a burning question remains: What new music there today is worth a listen? Sadly, Bourbon Street long ago devolved into an unruly, alcohol-soaked orgy of tourists and tribute bands. And given that most of the leading players from NOLA's glory years have passed, the annual New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival (aka Jazz Fest) now features Vampire Weekend, the Killers, Foo Fighters, Queen Latifah, and the Rolling Stones as headliners. A recent trip to NOLA, though, confirmed yet again that the clubs on Frenchman Street continue to keep the city's musical flames burning bright.

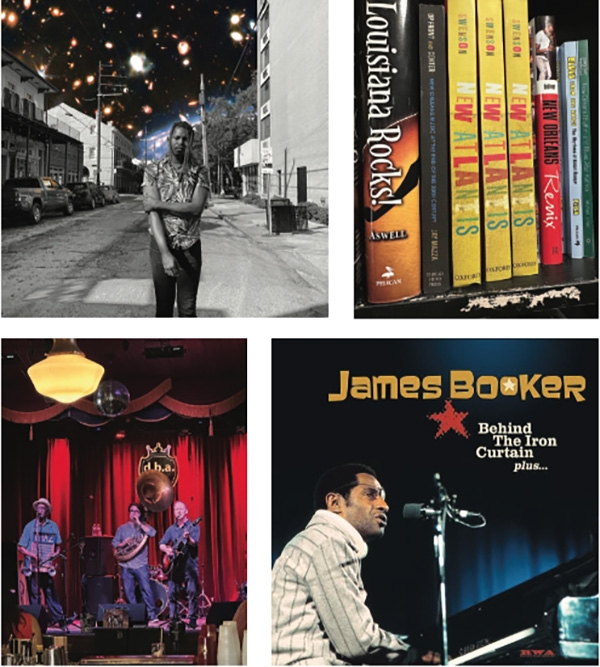

In late April, at D.B.A. New Orleans on Frenchman Street, I saw guitarist/singer Alex McMurray, who has a voice reminiscent of another famous New Orleanian, Randy Newman. A musical fixture in the city since the late 1980s, McMurray's latest project, Tin Men, features Chaz Leary, aka Washboard Chaz, on washboard and Matt Perrine playing sousaphone. Hit It!, the latest release (on CD, LP, and streaming) by this eccentric ensemble—from the stage, McMurray called it "America's premier guitar, sousaphone, and washboard trio"—was well-recorded at the Nappy Dugout (after the Funkadelic song), in New Orleans, by Mike Napolitano. The album includes a sousaphone-led version of Georges Bizet's "L'amour est un oiseau rebelle," from Carmen, that has to be heard to be believed.

Across Frenchman Street at The Spotted Cat, in a more introspective chamber-folk vein, was the Chris Christy Quintet. The Quintet's excellent self-titled five-song EP (released on CD) has Christy—who sings and strums a metal-bodied resonator guitar—supported by baritone saxophone, standup bass, violin, and cello.

The most interesting brass band I heard was one of trombonist Charlie Halloran's many musical projects, Charlie and the Tropicales. Its new album, Jump Up (CD, soon to be released on vinyl), moves from Afro-Cuban dance music to a soul-styled version of Willie Nelson's "Funny How Time Slips Away" and a transcendent cover of a New Orleans gem, "Gee Baby," co-written by the late New Orleans saxophonist Alvin "Red" Tyler.

New Orleans music new and old can be had nearby at the Louisiana Music Factory (louisianamusicfactory.com) and Euclid Records (euclidrecordsneworleans.com). My tastiest acquisition on this trip was a new five-CD set, Behind the Iron Curtain Plus..., which documents three concerts by the great pianist James Booker, performed in the 1970s by this most talented of NOLA pianists in Switzerland, East Berlin, and Leipzig. It's a highly recommended Booker extravaganza from RWA, the label of Bear Family Founder Richard Weize. It features surprisingly clear and detailed sound.

No column on the state of New Orleans music would be complete without a mention of my dear friend and longtime Stereophile contributor, the late John Swenson. I was happy to see several copies of New Atlantis, his masterful 2011 appraisal of New Orleans music and creativity post-Katrina, for sale at Louisiana Music Factory. No one loved NOLA's musical zeitgeist more than John, whose generous spirit epitomized NOLA's unofficial motto, laissez les bon temps rouler!

- Log in or register to post comments