| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

This sentence "And that's something I'd pay extra for." detracts from the objectivity of the review and makes it feel like, makes it too much, or by this it is actually an advertorial.

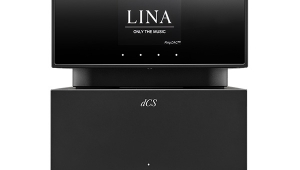

Anyway, nice to read the comparison with the Spring 3 3, but it is also completely taken out of context by the enormous price difference. The dCS is more than 4 times as expensive. Due to this large price difference, a comparison would actually be absurd, because the price difference is not a different level/segment/category, but the dSC is 2 (or perhaps more) levels/segments/categories higher. The fact that a comparison is made, AND the review does NOT say that compared to the dSC, the Spring 3 3 is not listenable (anylonger) makes the Spring 3 3 the clear winner. You would expect, and that would be reasonable with this price difference, 4 times, that the cheaper one really sounds rather so so, mediocre or even bad in comparison. What I get from this review is that the Spring sounds more lively and more fun, while the dSC sounds more realistic and tighter. But both just (a little). Everyone has their preference and it is up to the reader to decide. Still a really difficult choice with 2 price-wise comparable devices, but in this case it is not.