| Columns Retired Columns & Blogs |

Analog Corner #253: Mikey Gets Ortofon SPU'd Page 2

Most of what seemed to be missing were playback artifacts that ride along with the detail, along with the "visual" elements that help produce spatial context, including reverberant trails, initial transients, decay elements, etc. What was left were vivid, generously sized, richly drawn aural images laden with textures and harmonic vitality. Whether you hear this as thick and slow or as rich and full is a matter of sonic perspective.

Getz's breathy tenor saxophone was less in the clouds and more down on the ground, while the drummer Milton Banana's rim shots attained levels of woodiness I hadn't before heard from this recording. At the same time, the metallic aspects of the drum kit were present and well accounted for. Astrud Gilberto's iconic singing was also less breathy and ethereal than usual, but this perspective was equally valid and satisfying. Because of the woody richness of its sound through the #1E, João Gilberto's guitar was presented more prominently in the mix, with a mesmerizing lilt.

Then I switched to the #1S and played the album again. (I've been playing Getz/Gilberto, in one version or another, for more than 50 years, and I never tire of listening to it.) While the #1E hinted at the sound of a Shure M7D mounted on a Garrard Type A, the #1S brought me back decades, to my first stereo rig—and it was fine! Now the bass was really thick but still reasonably controlled, and the entire sound, while congealed in a Jell-O–like mold, made me feel more relaxed, as the reediness of Getz's sax floated thickly but lithely through a pleasing haze.

Yes, much detail was missing, but also gone were artifacts of mechanical playback, replaced by a luxuriously smooth sound and exceptionally "black" backgrounds. I began to understand the appeal of spherical styli—at least for playing Getz/Gilberto!

But because some say that SPUs are best with just this sort of vintage recording, I tried them with something relatively new: Eric Clapton's Slowhand at 70: Live at the Royal Albert Hall, a three-LP set with DVD that I highly recommend for music and sound (Eagle Rock EV307399). It's a bright, vibrant recording that, the louder I crank it up, the more I feel present on one of those seven London nights.

But hearing it through the SPU #1S was odd: like hearing the concert from the venue's outer hallways. Dynamics were squashed, the cymbals were squooshy and rivetless, and the sense of the hall's vast space was simply gone. Was this the #1S's conical stylus gliding over the high frequencies engraved in the grooves? Not my idea of a good time. However, I doubt there's an SPU fan interested in using this cartridge for playing this record.

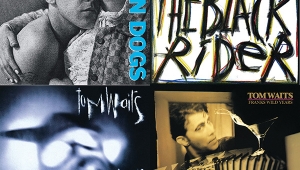

Which got me to thinking about a mono copy of the Beatles' Please Please Me (LP, Parlophone PMC 1202) pressed by British Decca, and sent to me by a very trusting reader. Unable to keep up with demand, EMI had contracted with Decca to press what some think were about 5% of the total units made of this album. It's now extremely rare, and can be identified by the "deep groove" label— ie, a circular groove, about 2.75" in diameter, that's impressed into the vinyl and can be seen and felt through the paper. I'd played this using the Miyajima Laboratory Zero mono cartridge, and it killed my original EMI pressing—but this Decca pressing was one record meant to be played with an SPU #1S (and my darTZeel preamp set to Mono).

Please Please Me always sounds somewhat bright and shrill, but the Decca pressing is fuller, more vivid, and definitely more dynamic. It sounded ideal through the #1S. Ringo's kick drum had perfect weight and texture, and the vocal harmonies were full and rich. In "Chains," there was so much "Georgeness" in the vocals! The Decca Please Please Me and the SPU #1S were made for each other.

That led me to some reissues from the Electric Recording Company, including a 10" mono recording of Yvonne Lefébure playing piano transcriptions of music by J.S. Bach (Pathé Marconi/EMI FBLP 1079/ERC ERC011), originally issued in 1955, that ERC has lovingly reproduced—including the dowel insert in the jacket's spine. People sometimes complain about the prices—starting at £300, or approximately $442—that ERC charges for their reissues, but the original of this one regularly sells online for more than $1500! An original clean copy of Leonid Kogan's recording of Beethoven's Violin Concerto, with the Paris Conservatoire Orchestra conducted by Constantin Silvestri (Columbia SAX 2386/ERC ERC005) sold just on eBay for $9189.97! And people complained that ERC's limited reissue edition of 300 copies (now out of print) cost $442?

In any case, the Lefébure disc is what the SPU was made for. It's not a great recording in terms of harmonic structure, but the simple production makes for great transparency and nuance. The SPU #1S silently sailed through the grooves, seeming to produce a direct connection to the modulations and effortlessly delivering the music.

I've got plenty of mono and vintage stereo LPs. I spent a few days playing them through these SPUs, and they all just sounded right and "of a time."

Universal Music is reissuing Frank Sinatra's catalog according to the Sinatra family's wishes, using high-resolution digital files instead of original master tapes. I was curious to compare an original pressing of This Is Sinatra: Volume Two (Capitol W982), cut for a 0.7-mil spherical stylus, with the reissue (Capitol 4 77044 4), mastered and pressed at Record Industry, in the Netherlands, from digital files created by "A. Nonymous," no doubt from the original tapes.

Would the SPU #1E, which is of lower resolution than more modern elliptical-stylus cartridges, obscure the differences (if any) between these pressings? One thing's for sure: whoever produced the files must have referenced an original pressing, because, tonally, the reissue is spot on. But otherwise, it sounded flat and dimensionless compared to the original pressing, which has depth and instrumental layering.

The five-disc reissue of The Nat King Cole Story (five 45rpm LPs, Capitol/Analogue Productions SWCL-1613) was a major achievement in audiophile reissues. Kevin Gray cut the lacquers, mixing directly from the original three-track tape, adding reverb from a chamber built on-site at the RTI pressing plant.

It's easy to argue that the reissue produces far greater transparency, detail, and spaciousness than the original (because it does!)—but played with the SPU #1E, the original does that time-travel thing, somehow turning a modern playback system into a vessel more appropriate for music recorded ca 1960.

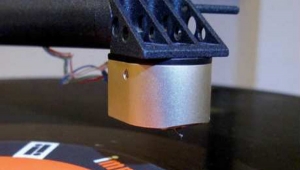

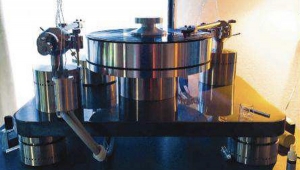

If I had to choose only one of Ortofon's two new SPUs, I'd go for the elliptical #1E. The differences between it and the #1S weren't profound, but the additional transient detail and dimensionality are well worth the extra $60. I wonder why Ortofon didn't make one #1 mono and the other stereo.

If you're considering buying one of these—and assuming you have a compatible tonearm, in terms of both the SME collet and a medium to high effective mass—I suggest using a tubed phono preamplifier and a loading of less than 100 ohms. Unloaded, the new Ortofon SPUs could sound bright on top; that, in combination with their rich, full bottoms, produced an unpleasant discontinuity of sound.

I'm still not thrilled to track stereo LPs at 4gm—but the sound was so rich, warm, flowing, and relaxing, the images so round and so generously sized, that I conquered my fears of worn record grooves and spent many pleasant evenings drinking wine and visiting the 1950s and '60s. If only I knew then what I know now!

- Log in or register to post comments